Give back my father, give back my mother;

Give grandpa back, grandma back;

Give me my sons and daughters back.

Give me back myself.

Give back the human race.

As long as this life lasts, this life,

Give back peace

That will never end

–Sankichi Toge[1]

There can be no denying the extents of the destruction and devastation experienced by the Japanese people by the end of the Second World War. Capped by the gravity of the destruction wreaked by the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, individual memories of survivors understandably point to experiences of victimhood. Certain events have, however, led to the expansion of the memory of the destruction and subsequent victimhood from being localized events to issues central to the Japanese consciousness. Examining the interplay of the social memory of the Japanese people regarding the destruction and the war, and its continuous negotiation through pop-culture, this paper seeks to examine how the narrative of victimhood has remained prominent in the years after the war through the 1980s. By examining historical events and the development of pop-culture through news, testimonials, testimonial fiction, and even science-fiction, in literature, art, television and film, we seek to gain insight into the nature of collective remembrance across generations. However, before we investigate the dynamics of the narrative of victimhood in the Japanese social memory, we must first understand the very framework of social memory itself.

Studies in social memory have often been interdisciplinary in nature. Traditionally, it has been approached from the perspectives of sociology, history, literary criticism, anthropology, psychology, art history and political science, among other disciplines.[2] According to Barry Schwarz, the emergence of social memory as a scholarly interest began between the 60s and the 70s in light of three dominant trends of the era: first, the call to challenge dominant historical narratives in the interest of repressed groups, second the emergence of post-modernism and their attack on linear history, truth and identity, and thirdly the emergence of hegemony theorists providing a class-based account of the politics of memory, highlighting memory contestation, popular memory and the contestation of the past.[3]

As such, there arose a desire to distinguish between dominant linear narratives in historiography and social memory studies. Halbwachs, a pioneer in the field of social memory, finds that “History is dead memory, a way of preserving a past to which we no longer have an ‘organic’ relation.”[4] In contrast to this, social memory would thus be “living” in that the “organic” relation continues to exist, and thus meaning can continue to be negotiated. This mirrors the traditional distinctions made by historians between history and memory in that history is engaged in the search for truth, while memory is engaged more on the level of meaning.[5]

The difficulty with understanding the framework of social memory is partly due to the lack of a definitive and universally acceptable definition for the term. For one, its very name can vary among different researches, including but not limited to the terms: public memory, collective memory, official memory, local history, and tradition. But what is shared between these differences in nomenclature is the distinction and interaction between the social and the individual memory.

Individual memory is characterized by cognitive psychology as the individual’s generative, interactive, ongoing mental process of retaining and recalling knowledge or experiences.[6] Individual memory is thus a pool of knowledge only accessible to an individual. Social memory, on the other hand would be a collective pool of knowledge shared by individuals through the negotiation of the meaning given to events and shared experiences. Unlike the perceived interiority of individual memory, social memory can thus be passed on to members of the social group.

On the level of memory, it is important to note that as that as in individual memory, the remembrance of the past does not entail unadulterated memories of past events, but must necessarily be reconstructed by our shifting selves as we shift affiliations through different groups, and as we change through time. As such, Halbwachs argues that social memory asserts that remembrance is always an active process of reconstruction and representation.[7] As such, it must be noted that memory is always situated in the present, meaning that any recollection of a memory is not the preservation of the past, but rather the reconstruction of the past in light of the understandings and definitions of the present.[8]

As is argued by Halbwachs, what this shows is that memory is not an exclusively interior individual activity; rather it always exists within a social context. As such, it is impossible to remember in a coherent fashion outside of the context of one’s participation in a group.[9] On this level, memories are socially framed for the meaning derived from individual memories always occurs in the context of groups such as the family, or the nation which one participates in. On the other hand, one’s participation in the group necessarily implies that one’s individual memories always participate in a discursive level towards the collective memory of the group.[10] Nonetheless, what this shows us is that on a level of interaction, the individual memory is thus necessarily in participation with some form of social memory. The participation in social memory thus necessitates the creation of “regimes of memory” shared by individuals within a group. This borrows Foucauldian notion of a regime of truth. In such a relation there is no universalizing fact or reality, but rather only discursive memories created and negotiated by the group. As such, the concern is not towards the facticity of the memory, but rather the regime of memory disseminated through the mnemonic artefacts that perpetuate it.[11]

Mnemonic artefacts, as Halbwachs claims, are the essential embodiments necessary for social memory. This is because social memories can exist only if they are located beyond verbal communication traditionally in the form of language, shrines, memorials, and statues, but as Godfrey and Lilley argue, may now be observable in the form of mass-media through literature, art, television and film.[12] They exist as tangible stimuli which provoke the collective remembering of a certain social memory through the context that it evokes.

As such, through the interaction between the discursive participation of individual memories, and the negotiated meanings of mnemonic artefacts encountered through mass media as pop-culture, it can be said that:

[Social] memory is an important process through which the collective identity of a community is constructed. Such memories are never univocal or unambiguous, however. Instead, [social] memory is always contingent and always contested, so that ultimately neither permanent nor stable collective identities exist. Especially through the collective rememberings shown in mass media, [social] memory can be contested and undermined with counter memories.[13]

In light of this framework, and the potential for continuous negotiation and contestation of social memories through counter memories, what this paper seeks to examine is thus, what social memory emerged on the level of the Japanese nation in the aftermath of the experiences of destruction in the Second World War? How did these social memories emerge? And how have these memories evolved through the generations proceeding from their conception? In order to address these questions, we begin our discussion by looking into the immediate aftermath of the war.

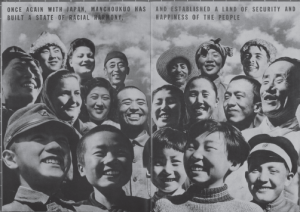

Still in the midst of the Second World War, two days after “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima, two national newspapers, Asahi Shinbun, and Yumiuri Shinbun covered the story publicizing the atrocious effects of the new bomb, seeking to incite anger against the United States. By the 11th of August, the Imperial Government publicly accused the United States of the use of inhumane weapons, with the two newspapers condemning the bombing as an act “against civilization and humanity” seeking to depict to the Japanese public through the political and public spheres that the country had been unjustly victimized.[14]

With the surrender of Japan to the United States, however, the angry protests were quickly dissipated. As a condition of their surrender, censorship imposed on the Japanese government disallowed it from publicizing the extent of the damage done to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As a result, Japanese who had not witnessed the bombing were initially kept uninformed about the destruction wrought by the bombs. However, even as the Japanese public eventually learned of the events that happened in the two cities, they were reluctant to treat the cities separately from other cities destroyed by fire bombs in the war. As a matter of fact, several members of the Diet did not wish to consider Tokyo whose casualties were three times higher than the cities as any different from the two.[15]

In the days that followed, the concept of an “A-bomb survivor” held no currency in the national consciousness. As a matter of fact, even in the localities, the notion of an “A-bomb survivor” was confined only to the sphere of the local medical practitioners treating the survivors. Due in part to the occupation, local politicians were not allowed to make political stands when discussing Hiroshima. Unable to make the association between Hiroshima and Japanese victimhood, and unable to seek a party culpable for the destruction, the image that emerged from the city was that of a depoliticized trans-national suffering. This meant that though Hiroshima was located geographically in Japan, the experience of destruction brought by the atom-bomb was not to be territorialized in Japan, but rather posed as a problem for all humanity.[16]

Under the constraints of their political circumstances, and in view of the reconstruction, Hiroshima was submitted to be reconstructed as a peace memorial city. “Members of the Diet saw that Japan could combine its so-called Peace Constitution, which renounced war as a sovereign right, with the atomic bombings so as to promote a new image of Japan as a peace loving country.”[17] As a result, commemorations of Peace Memorial Ceremonies remembered the people that were “claimed”, “put away” and “lost”, with such commemorations done in view of how the lives lost had laid the foundation for the transition towards Japanese peace and prosperity. Unfortunately, the founding of this foundational narrative carried a sense of conclusiveness—that there was full closure to the tragedy in statements that this will “never occur again”, pushing the ongoing tragedy of the disempowered “A-bomb survivor” to the sidelines, and forgotten.[18]

Still under the constraints of occupation, another aspect of the commemoration of “Hiroshima” during this period was the peculiar logic of the Atom-bomb as perpetrator. The bomb was “conceived as an actor in its own right and framed as possessing agency.”[19] Promoting a memory of victimhood-without-perpetrator, statements during commemorations of peace, were always done in a passive voice, without reference towards nationalities to blur the geo-political origin of the bombing.[20]

Elsewhere in Japan, however, the period of 1947 through 1949 saw the emergence of raw and deeply personal autobiographical writings Shinku Chitai, Furyoki, and Imupdru, expressing anger against militarism, and reflecting the general sentiment of the Japanese public, seeking to place the burden of responsibility for the war, the destruction and the suffering on the shoulders of the former regime.[21]

Focusing back on Hiroshima itself, the narrative recovery in light of the experience of destruction had also become dominant. Towards the end of the occupation articles about “A-bomb orphans” and “A-bomb survivors” had reached some level of national circulation through the newspapers. The memoir The Bell of Nagasaki, and testimonial novels Flower of Summer, Letters from the End of the World and City of Corpses describing the aftermath and destruction of the bombings of Hiroshima also gained popular circulation. However, the stories continued to be depicted in the absence of historical context and thus remained apolitical.[22]

Thus, due to the censorship employed during the occupation, mnemonic representations of “Hiroshima” rarely reached the Japanese public. The commemoration of the bombing was largely confined to the locality of Hiroshima. As a result, there was a distinction established between the memory of Hiroshima which sought to commemorate “Hiroshima” through transnational remembering, while the Japanese public bought into a “rebirth” frame, seeking to downplay and even forget the destruction brought by the bombing and instead emphasizing the recovery of Hiroshima.[23]

Japan regained sovereignty with its signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in September, 1951, and its subsequent implementation in 1952. In the absence of censorship, the story of “Hiroshima” began reaching the Japanese public. A-Bomb Children, Poems of the Atom Bomb, A-Bomb number 1: Photodocumentary of Hiroshima and Hiroshima: War and City were rushed into publication allowing access mnemonic artefacts in the form of essays, poems and photographs. Among these publications, one nationally distributed magazine called Asahi Graph made the most impact when on the anniversary of the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima; it published the special issue “The First Exhibition of A-Bomb Damage”. The issue showed photographs of the destruction in the immediate aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, despite making the mnemonic representations of the traumatic event more accessible on a national level, the photographs produced among its viewers the consciousness that the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki belonged to a distant past. The viewers were thus put in the position of being spectator to the memories, evoking a sense of pity towards the casualties, instead of being actors in the present, sharing the wounds of their victimhood.[24]

As a matter of fact, the pity pervaded the feelings towards the dominant mnemonic representations of the period. In this period the face of “Hiroshima” was depicted through the young Japanese women survivors dubbed the “A-bomb maidens”. The Japanese public took an interest in the women because of their keloids and other conspicuous wounds, which invoked a sense of drama and pity because the tragedy of their appearance had compromised the possibility for their happiness in marriage. Volunteers organized activities to much fanfare. With fundraisers aimed at helping them to get plastic surgeries. One newspaper article even captioned the activities with “May the scar of the A-bomb vanish”, as if surgery could treat the damage of the bomb. Assistance provided to the victims was seen as voluntary. As a result, discourse about the “A-bomb maiden” perpetuated the absence of culpability for those responsible for the A-bomb sufferers. [25]

A small minority of Japanese non-survivors, however, had begun to express discontent, at how the Americans justified the use of the Atomic-bomb. Their raising of criticisms argued as if “Hiroshima” was something uniquely important to all of the Japanese people. They sought to rally fellow citizens in solidarity through “Hiroshima” seeking culpability for the United States. Seeking to conjoin the Japanese national identity with the memory of Hiroshima, this minority laid out the third mnemonic solution in commemorating “Hiroshima”.[26]

By March 16, 1954, this third solution would dramatically pick up steam. The Japanese were shocked at the discovery of nuclear fall-out at Bikini Atoll, exposing tuna fish boat Lucky Dragon 5 to nuclear radiation. The discovery was done after the ship had unloaded and distributed the tuna to local markets. The contamination of tuna—a Japanese staple—led the entire nation to feel threatened by nuclear weaponry.[27] With the publicized radiation induced death of one of the crew members by September 1954, the entire archipelago was swept by anti-nuclear movements. “The phrase ‘thrice victimized by nuclear bombs’ was repeated in every signature-obtaining campaign against nuclear weapons.”[28]

In light of these initiatives, the A-bomb survivor was elevated to the level of the “unifying symbol for Japanese community’s atomic victimhood.”[29] The Lucky Dragon 5 incident created a critical shift in the people’s feelings towards the mnemonic representations, from a feeling of pity towards a feeling of sympathy, identification and solidarity. Shifting “Hiroshima” towards the national consciousness, they had defined it as the origin of the nation victimized by nuclear weapons.[30]

The new symbolic status of Hiroshima was best exemplified in August 6, 1954, five months after the H-bomb fallout. In an unprecedented display of solidarity, the Imperial Family, and Labor Groups attended the ceremony for the first time, with people across the political spectrum united in attending the commemoration.[31] The trauma of the fallout had led to the emergence of Hiroshima’s narrative of victimhood from the social memory of a localized community to the level of national consciousness.

The elevation of “Hiroshima” to the origin and core victimhood—a national trauma constitutive of their national identity of the Japanese people, has effectively opened up the negotiation of the remembrance of the experience of destruction through the war to a fully national scope. Having discussed the experiences of destruction and the emergence of victimhood as the dominant social memory on a national scale, we will now examine the evolution of these memories through the decades using the interactions between history, testimonial fiction and science fiction in pop-culture.

As is observed by Susan Napier, an expert in Japanese culture and literature, much of the post war Japanese science-fiction has followed a dystopian trend, often with apocalyptic touches. The notion of pop-cultural renditions of disaster is important as it gives insight not only into the progression of the genre, but also into the changing notion of a Japanese identity. Through the observation of science fiction, we can examine ideological changes both in the presentation of disaster, and the attitudes inscribed in the films towards disaster.[32]

Starting from where we ended our previous discussion, 1954 saw the release of Gojira. Known in the west more as Godzilla, the narrative is a chronicle of a scaly prehistoric monster awakened by American nuclear testing. In the story, his awakening as a radioactive monster leads to the death of thousands and the eventual destruction of Tokyo. It is only through the suicide of a humane Japanese scientist that the monster is destroyed and the world is saved.[33]

According to Napier, the film can be seen to operate on a number of ideological levels. First, supported by the historical experience of the tragedies in the nuclear-fallout of 1954, and the memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it demonizes the use of American nuclear science.[34] The film also builds on the memory of discontent against the American defence of the nuclear bomb, as critics note the explicitly stated anti-American sentiments in the film.[35] Through the depiction of the radio-active monster, the film also reveals its anti-nuclear agenda. The film thus fully embraces and reinforces the victimhood narrative prevalent during the era.

Second, however, it allows for the traditional happy ending, by allowing “good” Japanese science to triumph over the evil monster. Here, the external threat to the collectivity is addressed through the combined efforts of scientists and government, making it possible to achieve successful human intervention.[36] The film, offered to the immediate post war audience, allowed them to rewrite or at least reimagine their tragic wartime experiences. With images such as the destruction of Tokyo evoking memories of the recent war, the film also takes a decidedly pacifist stance.

Subsequently, these observations are also reflected in other forms of pop-culture during the decade. Films such as The Zone of Emptiness, War and Man, and Conditions of Humans reflected similar anti-war sentiments.[37] Most left wing producers conveyed political messages against war, and of a pacific nature. Many of the films tended to unify the Japanese through the common experience of suffering during the war. The narrative of victimhood, whose core continued to exist in the memory of Hiroshima, had thus expanded to the general experience of victimhood and suffering through war. Further, the promotion of anti-militaristic sentiment sustained the desire to hold the past regime responsible for the suffering.

Towards the end of the 1950s, however there a consensus seemed to emerge wherein it was no longer acceptable to write ‘detestable’ and ‘distasteful’ things about the war due to the emergence of political power groups such as the Association of the Families of the War Dead. On the one hand this level of negotiation arose from the sentiment that those who have suffered and lost loved ones should not have to suffer at the hands of writers who depict them in such a detestable manner. On the other hand, it also became politically inexpedient to condemn former high-ranking military officials who emerged as beacons to Japan’s economic miracle.[38] As a result, with the withdrawal of criticism against militaristic features of the past regime, negotiated into the post-war narrative of victimhood was also a deteriorating desire to hold the militaristic regime responsible.

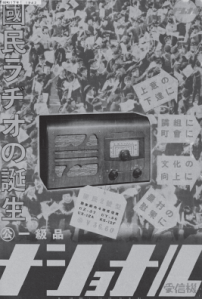

In such an atmosphere of increasing political conservatism, the mainstream, popular Japanese attitude of victimhood towards war was further developed. “The self-victimization of the Japanese, as a means of coming to terms with the past implied that the memory of the war needed to be sanitized in order to emphasize suffering instead of aggression.”[39] Starting from the 1960s, television became the most powerful form of mass media. In general, television programs about the war were commemorative in nature, and shown on dates of historic significance, such as the dropping of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the day of unconditional surrender. Minor changes in language, such as the term “end of the war” being used for August 15th instead of the term “day of defeat”, shows insight into how the memory of the war continued to be negotiated.[40]

The next major Japanese sci-fi release was the movie Nippon Chinbotsu. Released in 1973, the film is an evocation of the total submersion of the Japanese archipelago.[41] As Napier notes, the movie’s narrative is closely concentrated on the destruction of Japan through violent natural calamities. Further, the tone of the movie is less of excitement than it is a sense of mourning for the loss of the Japanese culture. One notable scene includes a pilot sent to fly over Osaka and take documentary photographs of the devastation. The eager scientists wait for the photographs; only find a swirl of clouds above the empty ocean. Impatient, they order the pilot to proceed to Osaka, only to get the chilling response, “this is Osaka”.[42]

In order to gain insight into how such a film of loss had become so popular in the Japanese consciousness in the 1970s, we look into the writer of Nippon Chinbotsu, Komatsu Sakyo. Sakoyo was born in 1931 and is thus part of the generation most devastated by the trauma of the Second World War. It is possible that in the aftermath of the trauma, the collapse and subsequent reconstruction, coupled with the economic boom of the 60s, a period characterized by social and generational conflict, the generation of Komatsu found success to be very transient.[43] At the same time Napier finds that the experience of the loss of the war and the rapid modernization/Americanisation that followed exposed the fragility of both the physical and cultural presence of Japan. “The film is essentially an elegy to the lost Japan.”[44] The film concludes with a high-altitude shot showing a fully submerged Japan, with the names of cities superimposed over a vast ocean, all that remains is its history and either written or collective memory.[45]

Again, looking at other manifestations of pop-culture during the period, there appears to be a concordance with the memory negotiated through this film. Though the film does not explicitly put to the fore the narrative of victimhood, it evokes the general feeling of the generation that had actually gone through the experience of the war. The reactions are thus split into two categories. First, there is the general feeling of weariness of the generation coming to terms with the destruction experienced in their childhood, and the sudden pace of modernization and abundance the present. This experience of weariness and being caught in between has also been rendered by comic book artist Yoshihiro Tatsumi in his works serialized at around the same time as the release of the film.[46]

Second, there is an emphasis on written and collective memory in the attempts of this generation to transmit their experiences towards the succeeding generations. For instance, as Shimazu notes, a quick survey of the TV programs between the 60s and 70s show that there were more programs on war during this period as compared to the succeeding decade.[47] As is noted by John Dower, part of the political debate in Japan “involves a struggle to shape the historical consciousness of the young, who have no personal recollection of the war.”[48] As such, aided by other forms of mass media, such as the television channel NHK, the 70s emerged as an age of abundance for “Atomic Bomb Art” depicting artistic representations of personal recollections of the atomic bombs. Along with this emerged children’s books devoted towards the remembrance of the destruction, perhaps, the most famous example of which is Barefoot Gen by Nakazawa Keiji.[49] What is particularly interesting about the boom of atomic art in this generation is the artists’ intention to depict the rawness of the experience, and their willingness to reintroduce the critique of Japan’s militaristic past. For instance, in the opening pages of Barefoot Gen, Japan’s militaristic and ultranationalist leaders are depicted in a bad light, as Gen struggles to cope with his traumatic experience to build a better world out of the debris.[50] Perhaps testament to the intensity of the rawness of the artistic works offered up as mnemonic artefacts, is the censorship of the art by artists Maruki and Nakazawa for being considered too cruel and too harsh.[51] And on this level we see an on-going contestation on the social memory of victimhood.

Likely because of such contestation and the changing demographics, by the 1980s, the mass appeal of war had begun to dwindle, with war programs appearing less and less frequently on the television.[52] As a matter of fact, even in film, the science fiction genre exhibited certain changes. For instance, Akira, the most notable science fiction film at the time had been directed to especially appeal to the younger demographics which have no experience of war. It does however, still present scenes which can serve as mnemonic artefacts for the memory of Hiroshima. For instance, the opening scene which explodes in a bright light, leaving only the destruction of a crater that haunts the entire movie, can be noted to be a reference to the historical experience of such a level of destruction (i.e. Hiroshima). What is different with Akira however is the nature of the second explosion which implies a “creative destruction”, one that is optimistic of the future, in its cinematic depiction of the creation of a new universe, and its focus on identity as the film concludes when it speaks “I am Tetsuo”.

Why then, are such perceptions so radically different in Akira as compared to Godjira and Nippon Chinbotsu? The answer may lie in the fact that Otomo himself was born after the war. As such, he belonged to the generation whose demographic is changing and challenging the long held beliefs of the “war generation”. With the displacement of the war generation as the key actors in the negotiation of the social memory of the war, it is hoped that the memory of victimhood can be balanced with memories of victimization through the coming generations.

[1] Toge was a survivor of the Hiroshima bombing, having been three kilometers away from the hypocenter during the explosion. He became a leader in the Japanese peace movement, publishing books opposing the atomic bombing and advocating peace. He died in 1953 at the age of 36. A monument has been erected in his honor in 1963, featuring the poem quoted above. This English translation of the poem is posted at the website of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum: http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/tour_e/ireihi/tour_23_e.html

[2] Olick, Jeffrey, and Joyce Robins. “Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practices.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1998): 105-140.

[3] Godfrey, Richard, and Simon Lilley. “Visual consumption, collective memory and the representation.” Consumption Markets & Culture 12, no. 4 (2009): 275-300.

[4] Olick and Robbins, 110.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Muskingam University Center for Advancement of Learning. “Learning Strategies Database: Memory Learning Strategies.” Muskingam University. n.d. http://www.muskingum.edu/~cal/database/general/memory.html#Background (accessed February 26, 2012).

[7] Godfrey and Lilley, 280.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Olick and Robins, 109.

[10] Godfrey and Lilley, 278.

[11] Ibid, 276.

[12] Ibid, 280.

[13] Hoerschelmann, Olaf. “‘Memoria Dextera Est’: Film and Public Memory in Postwar Germany.” Cinema Journal 40, no. 2 (2001): 78-97.

[14] Saito, Hiro. “Reiterated Commemoration: Hiroshima as National Trauma.” Sociological Theory (American Sociological Association) 24, no. 4 (2006): 353-376.

[15] Ibid, 360-361.

[16] Ibid, 361.

[17] Ibid, 361-362.

[18] Ibid, 362.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Shimazu, Naoko. “Popular Representations of the Past: The Case of Postwar Japan.” Journal of Contemporary History (Sage Publications, Ltd.) 38, no. 1 (2003): 101-116.

[22] Saito, 363.

[23] Ibid, 364.

[24] Ibid, 365.

[25] Ibid, 366.

[26] Ibid, 367.

[27] Ibid, 368.

[28] Ibid, 368-369.

[29] Ibid, 369.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid, 370.

[32] Napier, Susan. “Panic Sites: The Japanese Imagination of Disaster from Godzilla to Akira.” Journal of Japanese Studies (The Society for Japanese Studies) 19, no. 2 (1993): 327-351.

[33] Ibid, 331.

[34] Ibid, 331-332.

[35] Firsching, Robert. “Gojira.” Rotten Tomatoes. n.d. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/gojira/ (accessed February 27, 2012).

[36] Napier, 332.

[37] Shimazu, 104-105.

[38] Ibid, 105.

[39] Ibid, 106.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Napier, 332.

[42] Ibid, 334.

[43] Ibid, 334-335.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid, 335-336.

[46] Currently serialized by publisher Drawn & Quarterly as “Good-bye”, “The Push Man and Other Stories”, and “Abandon the Old in Tokyo”.

[47] Shimazu, 106.

[48]Dower, John. “Japanese Artists and the Atomic Bomb.” In Japan in War & Peace: Selected Essays, 242-256. New York: The New Press, 1993.

[49] Ibid, 242-243.

[50] Ibid, 248-249.

[51] Ibid, 248.

[52] Shimazu, 107.

Bibliography

Dower, John. “Japanese Artists and the Atomic Bomb.” In Japan in War & Peace: Selected Essays, 242-256. New York: The New Press, 1993.

Firsching, Robert. “Gojira.” Rotten Tomatoes. n.d. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/gojira/ (accessed February 27, 2012).

Godfrey, Richard, and Simon Lilley. “Visual consumption, collective memory and the representation.” Consumption Markets & Culture 12, no. 4 (2009): 275-300.

Hoerschelmann, Olaf. “‘Memoria Dextera Est’: Film and Public Memory in Postwar Germany.” Cinema Journal 40, no. 2 (2001): 78-97.

Muskingam University Center for Advancement of Learning. “Learning Strategies Database: Memory Learning Strategies.” Muskingam University. n.d. http://www.muskingum.edu/~cal/database/general/memory.html#Background (accessed February 26, 2012).

Napier, Susan. “Panic Sites: The Japanese Imagination of Disaster from Godzilla to Akira.” Journal of Japanese Studies (The Society for Japanese Studies) 19, no. 2 (1993): 327-351.

Olick, Jeffrey, and Joyce Robins. “Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practices.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1998): 105-140.

Saito, Hiro. “Reiterated Commemoration: Hiroshima as National Trauma.” Sociological Theory (American Sociological Association) 24, no. 4 (2006): 353-376.

Shimazu, Naoko. “Popular Representations of the Past: The Case of Postwar Japan.” Journal of Contemporary History (Sage Publications, Ltd.) 38, no. 1 (2003): 101-116.