Japanese Integration Propaganda and Shaping of a National Consciousness on the Heels of the Second World War

“The task of the Propagandist, especially in wartime is exactly that of Aristotle’s Rhetoric, ‘discovering in a particular case the available means for persuasion.’ War propaganda, like war itself, is amoral; its sole test is expediency. Its end is not enlightenment, but the attainment of specific results favorable to the propagandist.”[1]

For Imperial Japan and all the belligerents during the Second World War, the use of military propaganda is considered to have provided strategic advantage in the psychological war with the enemy. The use of leaflets and radio transmissions beyond enemy lines effectively weakened enemy morale and even encouraged enemy surrender at certain points during the war.[2] Looking at the entirety of the war effort, however, it is apparent that the use of use of wartime propaganda alone is not sufficient to characterize Japan’s experiences with the use of propaganda. For one, it is also the use of propaganda that rallied an entire nation to its central causes and principles even prior to the war. As such, in the examination of the Japanese use of propaganda during the Second World War, it is necessary to look into the development of propaganda outside the war period. This paper thus seeks to look into the development of integration propaganda, in the forms of education, advertising, and films, in Japan leading up to the engagements of the Second World War, and argues how through its manifestations in pop-culture, integration propaganda made possible the interweaving of the central narrative that fueled the civilian perception of the Japanese war effort.

Unlike wartime propaganda in the form of radio transmissions, and pamphlets which point directly towards a source and are often directed towards the combatants, current studies on propaganda have given the name “integration propaganda” to the more cultural experience of propaganda. Integration propaganda appears through the mainstream channels of cultural communication such as in films, music, and textbooks produced by the most influential people in society. Because of its transmission as a cultural experience, its nature as propaganda is obscured by the fact that it points toward a shared value or belief.[3] At the same time, its obscured yet omnipresent nature helps in the process of drumming up public sympathy through central causes, essentially consolidating viewpoints toward a central narrative. As Silverstein notes, “integration propaganda is important because no modern society can function long without, at least, the implied support of its citizens.”[4] In the case of Imperial Japan, the manifestations of integration propaganda took hold in the years prior even to the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

The roots of the formation of the formation of the modern imperial Japanese identity can be traced to 1868. With the Meiji Restoration, the rule of the Shogunate was ended together with the restoration of the powers of the emperor, in part due to the influence of Commodore Perry and the United States. The full emergence of the modern Japanese state, however, also draws from the deeply embedded opposition at the time, and the emergent actions by the Kokugaku, and Mitogaku schools of thought even during the Tokogawa period.[5] Towards the end of the 19th century, the state declared Shinto as a “supra-religious” state cult that must be subscribed to by every citizen. “The central role in the process of national unification fell to the institution of the imperial house. Its position, which the Nationalists declared to be unique and incomparable, was regarded as being based in the mythical tradition of antiquity.”[6]

This laid down the groundwork for the consolidation of beliefs towards a singular and unique national image that captures the “national essence”, a Japanese kokutai. The creation of this national identity enabled a cultural identification of a “Japanese spirit” to which as Antoni notes, allowed for a collective envisioning of “a Japanese ‘family state’ that joined all its citizens, or subjects, with one another on the basis of kinship, and then projected this mystical-mythical community onto the figure of the emperor as the father of this national extended family.”[7]

Because such distinctions were being established in the national psyche, the modernization of the state, together with the modernization of its technology and naval capacities to western standards had become acceptable while still maintaining a “Japanese Spirit”.

Folklore and Education

With the popular opinion among the Meiji Oligarchs seeking to compete with the West in order to beat it at its own game, the fledgling nation needed not only to modernize their technology to western standards, but also adapt to the western social structures of a modern nation. The goal was to establish a unified “Japanese” nation capable of entering the world stage as an imperial power. This thus necessitated the elimination of a country divided into territorial regions and social castes. However, it is in reaching out to the local populations that the formation of the national identity encountered its initial difficulties. Prior to the Meiji Restoration, peasants and citizens only thought within the bounds of their own territories, the concept of a larger unified “Japanese” community remained completely foreign to most. What was prevalent however was a martial culture that carried over from the prominence of the Shogunate. Thus, it was ideal that these martial virtues of the samurai were transferred to the Japanese people, shifting the territorial dispositions by establishing a military obligation between each citizen and the state.[8] However, even such an arrangement could not fully establish a central rallying narrative for the people. Thus, the primary means for the founding of a national identity was found to still lay in the institution of education.

In October 1890, the Imperial Government promulgated the “Imperial Rescript on Education” which intended to lay down a pedagogical tool for moral instruction (shūshin) in primary schools. “In reality the Rescript presented the moral foundation of the late Meiji State and thus the official foundation of kokutai thought, as a ‘non-religious religion’ of ‘magical power,’ as Maruyama Masao[9] has called it.”[10]

The Rescript and its subsequent renown as a quasi-religious document ensured that the spread of the imperial ideology was made obligatory to each citizen. Further, official commentaries on the rescript, including the Kokutai no Hongi of 1937, maintained a predisposition towards military training and moral education through the decades, while slowly adapting the citizenry to the changes in state ideology. [11]

Here, we are allowed to examine the role that primary education played in facilitating the use of integration propaganda. Beyond the role of educating the youth in reading and comprehension, the implementation of the Rescript allowed for the conditioning of the psyche of the Japanese citizen at a very young age. In its implementation of the Rescript, the curriculum covered various topics that were designed to be appropriate for the readers’ age group. Booklets appearing as early as 1933 illustrate the nature of these varied topics and the approach which was used to deliver them. As is documented by Antoni,

The first item… begins with a picture of a cherry blossom, the national symbol of Japan, and is followed by a picture of marching toy soldiers, with the caption below: susume susume heitai susume (“Advance, advance; army, advance!”). [This is followed by] a drawing of little children under a rising sun with an appropriate text and a portion of the Japanese national flag: hinomaru no hata banzai banzai (“The flag of the rising sun, forever, forever!”).[12]

Also appearing prominently through the first three booklets are various fairytales now commonly recognized throughout Japan as, Japanese “national fairytales”[13]. Through the collection of different fairytales capturing the experience of different regions in Japan, the educational institution was successful in establishing a common national consciousness. The third booklet begins the departure from the fairytale genre, including a story about Japanese mythology. The succeeding booklets focus more on prominent Japanese mythology, with the fifth booklet focusing only on the important myths of the Shinto Tradition. Booklets 6 and 7 conclude with the story of “the First Emperor of Japan (Jimmu Tenno) and conclude with the conquests and other deeds of the first great Japanese hero, Yamato Takeru, the ‘Brave Man from Yamato.’”[14]

The intertwining of the genres of the fairytale, legend, myth, moral instruction, and “historical references” were effectively utilized in order to establish with the young reader a connection with a central narrative and a national identity. The level of integration is such that for the Japanese, the process of gaining a cultural understanding of the political structures and military obligations necessitated referring back to one’s core traditions and beliefs which thus supplemented the mystical association between each subject and his Imperial government. As a matter of fact, the booklets provide insight not only to the relationship of Japan and the Japanese people, but also its ideological response to the world at the time.

As Antoni notes in his examination of the short story, Momotarō[15], “the fairy tale appears here as a political allegory of the confrontations of that time. Japan and its continental enemies are easily identified with the well-known figures of the fairy-tale tradition. It is thus easy for the recipients to subject the fairy tale to the clear-cut ethics of ‘good’ versus ‘evil.’”[16] Glimpsing even later into the war, the folk-story as a cultural-mythical foundation makes it easy to view the ideological associations between the Japan and the purity of the hero, Momotarō, the cooperative alliance with the dog, the monkey and the pheasant necessary to defeat the Devils and the Greater East-Asian Co-prosperity Sphere, and the Devils of Demon Island as the foreign western presence in Asia. Some allusions even go as far as depicting Hawaii as the Demon Island, providing a mythical justification of Japanese actions to the general public.

The integration of the mythology and the shared sense of national identity through education shows the ideological directedness of Japanese nationalism, with the mystical analogies of the past, shedding light to what the Imperial Government expected of its citizens in its present. The use of education as the primary platform for integration propaganda persisted until Japanese surrender at the end of the Second World War. With it, the development of its nationalistic ideologies, as in the Kokutai no Hongi of 1937, which continued to link the mythical and historical experiences of the country helped to usher in a generation of citizens, both military and civilian, committed to imperial success well into the Second World War.

Advertising

Along with the modernization of the Japanese economy, the 1920s saw the rise of major Japanese corporations competing for the fledgling Japanese markets. The growing consumer society provided a new platform for the shaping of the national consciousness through consumer products, and subsequently print advertising.

On the part of the corporations at this point, it is noted that it was clear to them that “they were not just product manufacturers, but arbiters of people’s taste who often worked in tandem with the state in directing consumer life and consumption habits through compelling visual strategies.”[17] Leading up to the 1930s, the field of commercial design opened up various opportunities for the development of the Japanese social and cultural identity through the creation of recognizable brands that used modernist imagery to promote their consumer products. During the early stages of the 1930s, the use of modernist photography in print advertising began exclusively as a pop-cultural phenomenon with the manipulation of images presenting a radical viewpoint, and a fresh perspective with its use of extreme close-ups, dramatic silhouettes and shadows evoking a sense urbanity, cosmopolitanism, rationalism and technological progress.[18] At the time, there was a very fluid distinction between advertising publicity and propaganda, with European and American firms using the two terms interchangeably.

Esteem for Japanese modernist photography in Japan was high in the 1930s. At the 1937 World Fair in Paris, Japan had presented an award winning, modernist National Pavilion, featuring large photomural collages featuring Japanese tourism. At around the same time, however, print advertising began to integrate the political context of the time, further blurring the line between publicity and propaganda.

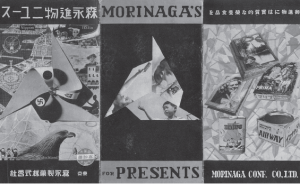

In 1937, Morinaga, a Japanese sweets corporation released a gift brochure featuring a montage technique simulating the image of a pinwheel bearing the national symbols of Japan, Germany and Italy. The middle of the brochure shows three young boys performing a salute, with the flip side presenting the Morinaga products. [19] The advertisement reflects the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936, creating an alliance between Japan and Germany, and a protocol between Italy and Germany in Rome in 1937 that would be the basis for the Tripartite Alliance creating the Axis Powers.[20]

By 1939, the further integration of modernist publicity techniques was exhibited when the Ministry of Commerce’s Industry’s Industrial Arts Research division, commissioning its wall with a painting entitled “Contemporary Industry”, highlighting Japan’s ship production, handicrafts and machine made textiles, machine industry, and aeronautics, envisioning modern industry where the state and daily life is intertwined.

The 1940s saw the creation of the Hōdō Gijutsu Kenkyūkai (Society for the Study of Media Technology, abbreviated as Hōken). The group tasked with the production of wartime propaganda effectively involved the biggest names in modernist photography at the time. Due to the call of the war effort, artists were able to divert their work into state-supported and state-sanctioned areas of artistic production in order to provide assistance in achieving the goals of the Imperial regime. With their ability to carry on with their work without difficulty, what was revealed was the nature of how advertising publicity and nationalist propaganda were essentially viewed by the artists as intertwined. To exemplify this, 1942, Matsuhita released a print advertisement of enthusiastic, young Japanese children, waving national flags to promote “the birth of the national radio”.[21] The advertisement promoted the radio as a revolutionary device which enabled communication and transmission of policy directives from authorities, communications between city and residents associations, cultural improvement and recreation.[22]

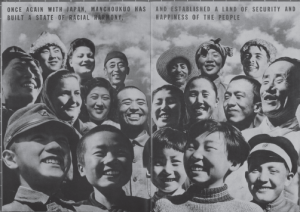

Beyond the traditional corporate advertisements, other, more explicit propaganda outlets such as magazines were also developed for the consumption of the general public. In 1943, the interior spread of the special Manchuria issue of the wartime propaganda journal FRONT[23] featured the output of veteran modernist advertising professionals, promoting the harmonious “quinque-racial” state of Manchukuo and the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

With veteran advertising professionals, assisting in the construction of the nationalist psyche, it can only be expected that the disposition of the regular consumer would further be conditioned by the exposure to the integrated advertising used to promote the consumer products. Access to corporate advertising thus exposed the consumer to specific opinions that were intended to be developed into the national consciousness, especially in preparation for the war.

Film

At the advent of the second Sino-Japanese war in 1937, the civilian population was again the focus of nationalist integration. This time the medium for integration sought to link the experience of entertainment with the ongoing war effort, drumming up support for the Japanese forces cast in the light of honorable heroes presented through mainstream films. It is noted that the period between 1938 and 1941 produced some of the best known Japanese war films to this day. With films like Five Scouts (1938), Mud and Soldier (1939) and The Legend of Tank Commander Nishizumi (1940), drumming up optimism and support for the war, the film industry took the role of helping to weave the principles behind the soldier’s war ethic into the central narrative developed in the Japanese psyche. To examine this further, we look into the research and analyses of Peter High on the three aforementioned films.

Released in 1938, Five Scouts brought film viewers to experience the stories of their countrymen currently engaged in the struggle with the Chinese. Rather than a grand narrative of the war, the film took on a more psychological perspective as it focused on the experiences of the company. For instance, though there is only one combat sequence throughout the film, death continues as a persistent topic among the soldiers, spoken of in in hushed tones and reverence with the death of a comrade invested in with heroic splendor.[24] Another notable include a speech by Lieutenant Okada illuminating the relationship between the soldiers, and the emperor, reinforcing the principles behind the mythological ideals in the Kokutai no Hongi of 1937. In the speech, he talks of how the “family circle” of the company overlaps the two spheres between family and country.[25] Another aspect of the film shows Lieutenant Okada reading the Rescript of 1938 to his soldiers, where at the end of the reading the scene is cut to the next, not showing any reactions from the soldiers, implying the task of obedience over reasoning when it came to the imperial directives.[26] In another speech, the role of the lieutenant in the film also prepares the audience for the instability of life under wartime conditions. Audiences are further conditioned such that in the face of committing their lives into a perilous action, some soldiers smile, leading to the creation of an ideological device in later Japanese war films, where the battlefield is viewed as the training ground of the spirit.[27]

Despite its commercial and critical success, the government was wary of the message delivered by the movie for the Japanese people. For one, the film did not depict an atmosphere of Japanese ultimate victory. Further some commentators viewed that the absence of a political center made the film accessible to a wide spectrum of admirers, leading to possible criticisms of how the imperial government required the utmost commitment of the soldiers in a reasonless war.

By 1939, the Imperial government promulgated the Film Law. “The Film Law imposed various regulations on making, distributing, showing, importing and exporting films. These regulations included the reinforcement of pre-production and post-production censorship, licensing and registration systems for all film workers, and a restriction on the number of films authorized film companies could produce in a year.”[28] Each film across all genres were thus made to reflect kokusaku (state policy), pointing to a more direct hand of the state in shaping the propaganda integrated through the medium of films.

Mud and Soldiers released in 1939 continued the use of film to allow the audience a glimpse into the experience of the Sino-Japanese war. Unlike Five Scouts which focused on the internal psyche of the company, however, this film took more interest at the bigger picture of the Japanese engagements, bringing the viewer merely to be caught in the rhythm of the drumming march of the soldiers. The opening sequence shows the audience the transmission of orders through the chain of command, finally reaching an individual Sergeant as he delivers the orders to his small group. This gave audiences an understanding, and even a participation in the chain of command.

The film continues to take a detached impersonal tone all throughout, using voyeuristic camera angles akin to a documentary. Such a documentary tone and method of capturing the events also impressed upon viewers the central role of the weaponry of war as a protagonist in the engagement. As is noted by High, “Tasaka’s Mud and Soldiers abounds in metaphorical images of the war as a grueling road that winds ever onward.”[29] The viewing public is thus conditioned to the overall nature of the experience of war, with the soldiers caught in between, even taking subtle delight in its experience.[30]

Legend of Tank Commander Nishizumi, released in 1940, sought to deliver the difficult task of depicting Nishizumi, an actual war hero hailed by the press a true gunshin (god of war). Set up as the bloodiest among the three films mentioned, the opening and subsequent scenes, made apparent the impression that every victory and every advance necessarily involved the loss of Japanese lives. The impression created is best captured by the character Nishizumi himself when he comments of the overall nature of the war, “this war is terrible, really terrible.”[31]

Despite the violence shown throughout the film, however, the film also seeks to present the humanist side to the Japanese soldier. In a scene depicting Nishizumi’s troops finding a wounded foreign civilian, carrying her baby, the troops comfort the civilian in her own language saying “We Japanese soldiers would never harm you peasants, we are your friends”, later even stating that the civilian’s baby is “not at all different from a Japanese baby.”[32] This referenced the ideological drive towards pan-asianism, and the Greater East Asian Co-prosperity sphere.

The role of the film as a propaganda device conditioning the minds of the Japanese people is also noted by High, stating that

As Mr. Average man from the battlefield, the “humanist” war film soldier had a home front propaganda role to play. Not only was he invariably brave when called to duty, he knew instinctively the right spiritual “posture” to take when confronting hardship and personal loss. Here, it was his fortitude more than his martial bravery, which made him a model for the national program of “steeling the will of the civilian population for a prolonged conflict on the continent.[33]

Other films released prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor also continued to promote the “national spirit” with its highlighting of national traditions, and promotion of values of self-sacrifice, filial, piety, and the subscription to the feudal hierarchy. Beyond Pearl Harbor, the use of film as a medium of integration continued well into the Second World War. Between 1942 and 1945, combat films and home-front dramas became increasingly in abundance. Expanding beyond the Chinese setting, the films began to depict stories, especially victories all over the Pacific front.[34] The seeds for anti-western sentiments were also sown with the general public through the films like Opium War. In fact, during the period, though the films continued to be explicitly written and distributed for Japanese audiences, the films also served as propaganda for distribution in Japanese controlled territories, seeking to condition regions under military occupation and displacing Hollywood films that dominated the Asian markets.[35]

By 1943, however, it is noted that war films depicting Japanese victories dwindled, as a reflection of the actual Japanese successes on the Pacific front. The triumphant tone seen in the movies in the past two years were now replaced themes of personal sacrifice, determination, and endurance despite the wartime constraints. By 1944, the only historical film released was Kakute Kamikaze Wa Fuku (The Divine Wind Blows) which referred back to the audiences’ integrated mythological history, telling the tale of the Divine Winds that repelled the overwhelming forces of the invading Mongols.

The use of film in integration propaganda, especially in light of the film law of 1939, sheds light on the development of the psyche of Japanese civilians to embrace the values of the soldier, the principles and the experiences of the broader war itself, preparing the civilian populations for the impending experiences of war. Here, even the experience of entertainment has been co-opted to project and continuously accept oneself as a subject to the national agenda, reinforcing nationalism as intertwined with leisurely experiences.

In conclusion, examining the Japanese historical experience of integration propaganda in the fields of education, advertising and film reveals to us that the founding of a central narrative and the Japanese kokutai within the general public was molded by their experience of pop-cultural propaganda. Beyond the common conceptions that the “Japanese Spirit” was shaped mostly by adapting the Bushido code of the past era, the obedience and even fanaticism to the central narrative crafted by the modern Imperial Japan had been woven through the use of civilian experiences in education, consumption and entertainment. The loyalty to this formed nationalistic consciousness emerged in that everywhere a civilian looked, be it from film, to the magazines and brochures, to educational pamphlets, and even to public musical performances, each Japanese citizen was reminded of virtues and values that championed the Imperialist ideology, and its ideals often reinforced. As one looked through one’s education, the basic narrative of their purpose based from the mythic-historical legacy was established, their consumption of goods pointed to the political stance of the nation as a world player, and their experience of entertainment characterized the moral values and virtues expected of each citizen.

It can even be said that as early as 1933, the imperial outfit’s use of integration propaganda had already began to manifest preparations for long-term warfare. Further, it can be said that looking at the Japanese experience of pop-culture, the level of integration, and preparedness for the eventuality of war had already been demonstrated in its fullness as early as 1939. Looking into the experience of music, by 1939, “The Mother at the Kudan Station” (Kudan no Haha) had been the most popular song in the Japanese consciousness. The song is about a mother who gets off at a train station where her dead son is to be honored. As a newcomer to the city, she wanders the streets fretful and confused, yet her experience is not viewed with tragedy, but rather with a humble pride. To the people, she became a model of fortitude, an implication that many, many more will follow willingly in her footsteps.[36] Such was the case that at the advent of Japan’s entry into the Second World War in the early 1940s, the Japanese people had already been psychologically conditioned as to the purpose of their actions, and their roles and obligations in the impending war.

The interweaving of the nationalist narrative into various aspects of their lives was so effective that it must not come as a surprise that the thought of surrender was very far from the Japanese individual’s psyche. The use of the language of destiny, necessity, and obligation in everything they encountered through their cultural experiences meant that the Japanese people would fight until the bitter end.

[1] Lomas, Charles. “The Rhetoric of Japanese War Propaganda.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 35, no. 1 (February 1949): 30-35.

[2] Schmulowitz, Nat, and Lloyd Luckmann. “Foreign Policy by Propaganda Leaflets.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 9, no. 4 (1945-1946): 428-429, 485-493.

[3] Silverstein, Brett. “Toward a Science of Propaganda.” Political Psychology 8, no. 1 (March 1987): 49-59.

[4] Ibid., 50.

[5] Antoni, Klaus. “Momotarō (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Shōwa Age.” Asian Folklore Studies (Nanzan University) 50, no. 1 (1991): 155-188.

[6] Ibid, 157.

[7] Ibid, 158.

[8] Ibid, 159.

[9] Masao is a Japanese Political Scientist, and theoretician on culture and the nation-state.

[10] Antoni, 160.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid, 160-161.

[13] The fairytales include: Shitakiri suzume, Usagi to kame, Momotaro, Saru to kani, Nezumi no yomeiri, Kobutori, Hana-saka jiji, Issunboshi, Kachikachi-yama, Nezumi no chie, Kin no ono, and Urashima Taro

[14] Antoni, 161-162.

[15] The full version of the story is available in Appendix 1.

[16] Antoni, 162-163

[17] Weisenfeld, Gennifer. “Publicity and Propaganda in 1930s Japan.” Design Issues 25, no. 4 (2009): 13-28.

[18] Ibid, 14-15.

[19] The advertisement is attached as Appendix 2 Figure 1.

[20] Weisenfeld, 21.

[21] The advertisement is attached as Appendix 2 Figure 2.

[22] Weisenfeld, 19.

[23] An image of the spread is attached as Appendix 2 Figure 3.

[24] High, Peter. The Imperial screen: Japanese film culture in the Fifteen years’ war, 1931-1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, 192-222

[25] Ibid, 198.

[26] Ibid, 201.

[27] Ibid, 199.

[28] Washitani, Hana. “The Opium War and the cinema wars: a Hollywood in the.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 4, no. 1 (2003): 63-76.

[29] High, 216.

[30] A soldier, is at one point depicted as saying “God, I love war.”

[31] High, 214

[32] Ibid, 215.

[33] Ibid, 216.

[34] Desser, David. “From the Opium War to the Pacific War: Japanese Propaganda Films of World War II.” Film History (Indiana University Press) 7, no. 1 (1995): 32-48.

[35] Washitani, 64.

[36] High, 216.

Bibliography

Antoni, Klaus. “Momotarō (The Peach Boy) and the Spirit of Japan: Concerning the Function of a Fairy Tale in Japanese Nationalism of the Early Shōwa Age.” Asian Folklore Studies (Nanzan University) 50, no. 1 (1991): 155-188.

Desser, David. “From the Opium War to the Pacific War: Japanese Propaganda Films of World War II.” Film History (Indiana University Press) 7, no. 1 (1995): 32-48.

High, Peter. The Imperial screen: Japanese film culture in the Fifteen years’ war, 1931-1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

Lomas, Charles. “The Rhetoric of Japanese War Propaganda.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 35, no. 1 (February 1949): 30-35.

Schmulowitz, Nat, and Lloyd Luckmann. “Foreign Policy by Propaganda Leaflets.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 9, no. 4 (1945-1946): 428-429, 485-493.

Silverstein, Brett. “Toward a Science of Propaganda.” Political Psychology 8, no. 1 (March 1987): 49-59.

Washitani, Hana. “The Opium War and the cinema wars: a Hollywood in the.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 4, no. 1 (2003): 63-76.

Weisenfeld, Gennifer. “Publicity and Propaganda in 1930s Japan.” Design Issues 25, no. 4 (2009): 13-28.

APPENDIX 2